- Home

- Arthur Ransome

Peter Duck Page 15

Peter Duck Read online

Page 15

“We’ve done it all right,” said Captain Flint. “That’s one, two, three steamers, two cargo boats and a tanker … more of them hull down … there’s another of those French fishermen … Not a sign of the Viper. No. We’ve done it.”

“Hope he’ll like Dublin,” said Nancy.

“Or the North Pole,” said John. “The farther he goes the better.”

“Aye,” said Peter Duck, after a slow careful look all round the horizon. “Seems we’re quit of him, right enough.”

“Thanks to you, Mr Duck. We’ve got clear from him, and we’ve got one of his crew instead of him having one of ours,” said Captain Flint gleefully. “Well, Bill, I wonder if Black Jake’s missing you much?”

“There’s nobody aboard the Viper what anybody can lay into now.”

“So you think they’re cruising round the Wolf Rock looking for you with a rope’s end?”

“Well, I ain’t there, anyhow,” said Bill.

*

Dinner that day was hours late, a joyful but a most unsteady meal. The sea was getting rapidly worse and worse. They had had a taste of wind that last night coming down Channel, but then the wind had been off the land. Now, running south for Spain, they were exposed to the full drift of the Atlantic. Old Peter Duck was enjoying it. “I knows this bit of water,” he told the mates, while they were giving him his dinner. “By Ushant right down across the Bay I knows it. I were in them Frenchy boats fishing round here when they give me to the skipper of the Louisiana Belle for a bag of tobacco. But I telled you that yarn before. First an easterly, then a fog, and then a blow from the nor’-west. We’ll be hove to before night, but we’ll be getting better weather in the morning.” He had his dinner, lit his pipe, and went up again to take the wheel while Captain Flint came down.

Captain Flint had been the first to ask for food, but Susan said it was waste of time cooking for him if he would talk instead of eating. He came down with two volumes of Hakluyt’s Voyages from the shelf in the deckhouse, and he had brought the big chart down again, and nothing would stop him from using plates to keep the chart spread out over the fiddles while he was looking first in one of the books and then in the other. But in the end he remembered that Mr Duck had been up most of the night, and he sent John and Bill up to take the wheel, and gulped down his food and hurried after them.

He found them together at the wheel when he came on deck, but Peter Duck had not yet gone to his bunk. He was standing in the deckhouse, leaning out of the doorway, watching the two boys at the wheel and looking at the weather.

“Blowing up quick, it is,” he said when he saw Captain Flint. “Wind after fog. Always the way. It’s a right wind for us, if it don’t blow up a bit too hard.”

“There’s no shelter to look for out here,” said Captain Flint.

“We don’t want none,” said Peter Duck. “With every mile we make to the southward we gets deeper water. We don’t want no better. Get her into deep water and she’ll ride out anything. It’s shoal water makes the trouble and drowns poor sailormen. We’ll best be putting a reef or two in her sails, and then if it don’t get no better, we can heave her to for the night, and she’ll lie as snug as a gull.”

Reefing was no easy job but it was done, at last, and then, with Captain Flint on deck, the old sailor went to his bunk and lay down for a minute or two, but he could not stay there. He came out again and stood there, watching the way the little schooner ran.

“Aren’t you going to get a bit of sleep, Mr Duck?” said Captain Flint.

“Time enough for sleep later on,” said Mr Duck.

Hour after hour she ran on, easier now under her shortened sails. But the sea was growing steadily worse, and the wind blew harder and harder. The mates tried washing up on deck after dinner, but so much water was coming aboard that it felt rather as if they were being washed up themselves. Roger brought Gibber up to have a look at things, and sat with him on the top step inside the companionway. But a bucketful of spray flew in there and soaked him as well as the monkey, and they had to close that door to keep the saloon dry. They had already closed the skylight. It was oilskins that afternoon for everybody who came on deck. Those who were not at the wheel found shelter for themselves under the lee of the deckhouse and tried to keep the water that blew across the roof from pouring down their necks. There were always two at the wheel, and all the time the spray came blowing over, slap, slap, against their oilskin backs. The motion grew worse again, and Susan and Peggy, taking turns with it, had a hard job to keep the kettle in its place when they wanted a drop of hot water. At last, just as it was falling dark John heard Peter Duck, who was at the wheel with him, shout to Captain Flint who was standing close by: “She’s done very well, she has. How’d it be if we was to heave to now, for a quiet night, before anything carries away?”

“What if that fellow races us across?” said Captain Flint, who, now that he was bound for Crab Island, hated the idea of stopping even for a moment.

“He’ll have to come down this way,” said Peter Duck, “unless he wants contrary winds the whole way across. There’s no good way but the old sailing ship track by Spain and Portugal to the North-east Trades away down by Madeira and the Canaries. If the weather’s bad for us, it’s worse for him. If the Viper’s not hove to at this minute, somewheres north of the Land’s End, Black Jake’s wishing she was. She’s a flyer, the Viper, but she won’t carry sail in bad weather.”

“Shall we ever have it worse than this?” Nancy asked, snuggling down into her oilskins.

“We’ll be having good weather when we get by Finisterre,” said Peter Duck, “but it won’t last as bad as this beyond the morning.”

“So long as it doesn’t get any worse, it’s all right,” said Nancy, who was very pleased indeed to find that she was not feeling sick.

“Well,” said Captain Flint, “you know the Bay better than I do. And there’s one thing about it. We could all do with a bit of sleep after last night.”

Bill earned good marks from everybody in the half-hour of tremendous business that followed. He never quite managed to be in two places at once, but worked so hard and made himself so useful that it almost seemed as if he had. When they had done, and rested, panting for breath, they had the heavy booms lashed down in their places, stowed all the ordinary sails, and left the Wild Cat under a tiny storm-jib and a trysail, balancing each other, so that she lay quiet, meeting the waves as they came but no longer driving on her way.

“Beautiful she lays,” said Peter Duck, when all was done. Nobody on land would have thought so, but aboard the Wild Cat it felt like a peaceful holiday after the last strenuous hours of the evening. No more water was coming aboard. The lurching of the vessel was less violent. But the mates did not try to cook anything for supper. Everybody cheered them when they came staggering below with a huge jug of boiling cocoa.

*

Just before Titty and Roger went to their bunks for the night, they were allowed on deck for a last look round. It was a wild sight. Now and then when the schooner lifted on the top of a great sea, they caught a glimpse of a steamer’s lights far away. There was nothing else to be seen but flying clouds overhead and the white rolling tops of the waves. Yet the Wild Cat was comfortable enough. Hove to, under her two small sails, the little schooner seemed to be at home in the midst of the tumult. She seemed to be picking her way almost in her sleep in and out among the mountain ranges of the sea. Alone in the dark, her lights burning confidently and brightly, the Wild Cat lay resting, as Peter Duck had said she would, easy as a sleeping gull upon the heaving waters.

Bill, too, to his surprise, had been sent off to his bunk soon after supper.

“Everybody’d better take their chance of a good night’s sleep,” said Captain Flint. “Wheel’s lashed. Mr Duck and I’ll keep a look out. Off you go, Bill. No point in sitting up with your eyes closing. You did good work with those reef points, my lad. Off you go now. You can get up as early as you like in the morning.”

&nb

sp; In the saloon, after the others had gone, John, Susan, Nancy, and Peggy sat at the table under the swinging lamp. For a little they talked of the voyage ahead of them and of Mr Duck’s island, but the talk soon turned to Bill, who, after all, was not so far away.

“He’s awfully good at going up the mast,” said Nancy.

“Anybody can tell he’s been to sea before … really to sea,” said John.

“It must be awful in trawlers,” said Susan.

“I don’t suppose he thinks anything of this,” said Peggy.

“Of what?”

“Being hove to in a storm,” said Peggy, grabbing the table as the Wild Cat seemed to pitch and skid sideways both at once.

“Well, it isn’t half bad,” said Nancy.

“He’s going to be useful in all sorts of ways,” said John.

“What would have happened to him if we hadn’t picked him up?” said Peggy.

“Drowned, probably,” said Nancy. “Black Jake hadn’t even left him an oar.”

“Sh,” said Susan. “He may not be asleep.”

Holding firmly to the table, the bulkhead and anything that came handy, the four of them crept towards the cabin that had once been labelled hospital, but now bore a new label, “Bill. A.B.” on its half-opened door. John looked in. The others listened.

“He’s gone to sleep in his clothes,” said John.

“Oh, I never thought of it,” said Susan. “That’s my fault. He’ll have to have somebody’s spare pyjamas.”

“I’ll get him mine,” said Peggy.

“It’s no good waking him now,” said Susan. “He’s probably horribly tired.”

*

Upstairs in the deckhouse, Peter Duck lay in his bunk, darning socks. Susan had offered to darn them for him, but he had said that darning socks was the sort of work he liked to do at sea. Captain Flint sat at the chart table, playing patience, swaying in his chair to meet the motions of the ship. Miss Milligan was the patience he was playing and he had brought it out twice running. After each game he had gone out into the wind and made the round of the deck to see that everything was all right.

“If I bring it out three times running, Mr Duck,” he said, “if I bring it out three times running it’ll show Fate’s taking a hand in the game and we’re going to lift that treasure of yours, eh, Mr Duck, Black Jake or no Black Jake?”

Mr Duck’s darning-needle was working more and more slowly.

“Grand sailing in the Nor’-east Trades,” he said.

A few minutes later, Captain Flint swung round in triumph.

“Three times running, Mr Duck,” he cried. “You couldn’t have a clearer sign.”

But Mr Duck’s sock had dropped on the floor, with the darning-needle fastened to it at the end of a long painter of grey wool. Mr Duck had slipped down in his bunk. His mouth had fallen open a little. His breathing had become more regular and was beginning to sound its usual musical note. Mr Duck was asleep.

Captain Flint picked up the sock, spiked it with the darning-needle, and dropped it into the bag-of-all-sorts that was hanging from the end of Mr Duck’s bunk. Then he got up and went out once more into the night.

“Three times running,” he said. “Three times running. What, it’s sure as if we had the stuff already stowed aboard.”

CHAPTER XV

BILL FINDS HIS PLACE

BILL STIRRED IN his bunk, and waked suddenly to disturbing comforts. What was this soft blanket at his chin instead of the hard canvas of the Viper’s sail locker? Bill woke all of a piece, everywhere at once, like a little animal, and with a single swift wriggle pressed himself hard against the planking at the back of his bunk. Close in the angle of wall and floor, whether in a bunk, a sail locker or else-where, a boy is fairly well protected against ropes’ ends and such things. But no rope’s end searched him out or thudded on the planking. No. He was mistaken. He had not overslept. Nobody was cursing him for not having lit the galley fire. There was nobody there. He was alone, with a couple of warm, brown blankets in a box in which he could stretch without coming anywhere near touching either end.

He remembered where he was, and a slow grin spread over his broad, freckled, red face.

“Wonder who’s lighting the galley in the old Viper?” he thought, and then he shivered, remembering the fog of yesterday, the drifting dinghy, the noise of sirens and foghorns, the sudden shadow of a ship’s bows coming down on him out of the fog, the rope thrown to him, and then the surprise of seeing Mr Duck at the wheel, and of finding what vessel it was that had picked him up. Better could not have happened to him than that.

Light came into the little cabin from the skylight over the alleyway and saloon, but Bill could not see out. He had no need. He had not been born on the Dogger Bank for nothing. He knew at once, from the motion, that the Wild Cat was still hove to. That was all right. No hurry. And then Bill chuckled to himself.

“Cap’ns and mates an’ all,” he was thinking. “Why, if Black Jake had knowed there was nobody else aboard he’d have had Mr Duck out of the Wild Cat in two shakes, so he would … Not but what they ain’t a handy lot for children.”

There was no one to remind him that he himself was not as old as Nancy. He felt a hundred in comparison with any one of the crew. The skipper and Peter Duck seemed to him right enough. The skipper could handle the ship and everybody knew that a better seaman than old Peter Duck had never sailed out of Lowestoft pier heads. Common talk that was. Everybody knew it. But the rest of them! “Cap’ns and mates! Cap’ns and mates! Why, Black Jake and his gang’d eat ’em. It’s a good thing as I come aboard. Makes three of us, anyway.”

He reached up out of the blankets to the little rack above his head and took down from it the new toothbrush that Susan had given him the night before. He looked at it curiously. “Cap’ns and mates!” he said again, “and they don’t know how to clean between their teeth with a bit of rope yarn!”

But just then someone stamped on the deck overhead, and he heard John and Roger struggle out of their cabin and race for the deck. Toothbrush in hand, he was after them in a moment. Queer sort of clothes they seemed to have on, the sort of thing you’d see minstrels wearing, giving a show on Yarmouth Pier. He dashed up the companion after them, and out on deck.

“Morning, Captain Flint! Morning, Mr Duck,” they said as they hurried, not too steadily, forward along the heaving deck. He said the same, and hurried after them, getting a nod from the skipper, on the way.

Captain Flint and Peter Duck were busy, with sextant and chronometer, trying to get an observation. The sun was showing now and then through scurrying patches of grey cloud. There was not quite so much white water as there had been, and though the wind was still strong it was no longer lifting whole tops of waves.

“Come on,” shouted John, flinging his pyjamas down the hatch and swinging a canvas bucket over the side.

“Come on,” said Roger, tearing off his pyjamas, throwing them after John’s, ready for the bucketful of salt sea water that John emptied over him.

Those queer clothes of theirs certainly did seem to come off easily. Bill pulled at his ragged jersey, after wedging his jacket in a safe place among the halyards. He struggled out of his patched blue trousers. He pulled off the vest that for some weeks had been keeping him warm underneath. It was pretty cold, but if these children could stand it, he would.

“Come on,” said Bill, bracing himself to meet the bucketful that got him full in the face.

“Come on,” said John. “You take the bucket and chuck one at me … I say, you do know how to dip full buckets. I never get a really full one first chuck. Hullo! Haven’t you got a towel? Skip along, Roger, and bring one up. Let’s have the bucket. I’ll try to give you a really good one, too.”

A few minutes later Bill rubbed a good deal of himself dry with the towel that Roger pushed up through the hatch. Somehow or other he forced damp arms and legs into his clothes and felt surprisingly warm. He would do the whole thing properly while he was abo

ut it. He took the canvas bucket and filled it once more over the side. Then, pulling out the toothbrush, he dipped it in.

“No need for that,” said John, thinking of the taste of salt water. “Susan always gives us a ration of fresh for teeth.”

“I was just giving it a bit of a damp,” said Bill. That was wrong, was it? Well, a fellow couldn’t learn all these tricks at once. He glanced hopefully aft. Perhaps they would be making sail. If it came to sails he’d be one up on these children again. Not like toothbrushes!

But he had to wait till after breakfast for his chance, and then it did not come with sails.

Breakfast was late. But the queer thing was that there was no shouting at anybody, though everybody must have been hungry. The two mates just came pelting up, saying they were sorry, and bolted round the corner into the galley, where the skipper himself had put the porridge on to boil in the double cooker. There was no doubt about it. The Wild Cat was a very queer ship indeed. And later, when everybody but the skipper was down in the saloon, and Susan was ladling out the porridge, while Peggy was sluicing hot cocoa into the mugs, Bill looked from face to face and wondered. There was probably a catch about it somewhere. But old Peter Duck blew the steam off his cocoa and swigged it as if everything was perfectly usual. Well, folk did say that there was nothing about the sea that Peter Duck didn’t know. Life in the Wild Cat was a bit different from life in a Grimsby trawler, and still more different from those days in the Viper which had left a fair lot of bruises on Bill but he supposed that the longer he lived the more he was likely to learn. With one eye on Mr Duck, he blew the steam off his own cocoa, and pitched the porridge into his gullet, in the same calm, business-like manner that he admired in the old seaman. As for those children … When breakfast was over and Captain Flint had come down for his, while Mr Duck had gone on deck, and when Captain Flint had gone, too, and the crew were alone in the saloon, Bill saw his chance of showing that he, too, knew something. It came with a word that Nancy let slip about the horrible way in which the Wild Cat was shaking things up. Bill felt in his pocket. Yes, he still had that quarter plug of black tobacco ….

Peter Duck: A Treasure Hunt in the Caribbees

Peter Duck: A Treasure Hunt in the Caribbees Racundra's First Cruise

Racundra's First Cruise Great Northern?

Great Northern? Swallowdale

Swallowdale Swallows and Amazons

Swallows and Amazons Winter Holiday

Winter Holiday Missee Lee: The Swallows and Amazons in the China Seas

Missee Lee: The Swallows and Amazons in the China Seas Pigeon Post

Pigeon Post We Didn't Mean to Go to Sea

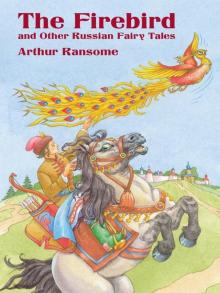

We Didn't Mean to Go to Sea The Firebird and Other Russian Fairy Tales

The Firebird and Other Russian Fairy Tales Coot Club

Coot Club The Big Six: A Novel

The Big Six: A Novel Six Weeks in Russia, 1919

Six Weeks in Russia, 1919 Secret Water

Secret Water The Big Six

The Big Six Missee Lee

Missee Lee Peter Duck

Peter Duck The Picts and the Martyrs

The Picts and the Martyrs